Got into work the other day and turned on NPR in the back room. They announced an interview coming up in an hour with Charles Frazier about his new book,

Thirteen Moons, on Diane Rhem's show.

I'd read Cold Mountain twice - a rare feat for me in these years exiled from idle youth; nowadays every hour an opportunity - or scramble - to get something done. Now his second book was out after 9 years. No freakin' way was I going to miss an interview with Frazier, so I concocted a "switch" in my work schedule which enabled me to work in the backroom and listen to the radio.

Weeks before this, strangely enough, I found out that an acre of land had come down to my cousins and I from my mother's side of the family - that lay very near Cold Mountain. My mother Leora, and her brother Hugh, had lived in a cabin there for a short time with their grandmother as kids in the 1920's.

I was pleased to hear that Frazier's speaking voice was easy on the ears and his responses as deliberated and detailed as his writing; unassuming, polite, and natural in the southernly-at-best manner. For a guy with an 8 million (!) advance on Thirteen Moons (following his success with Cold Mountain) he sounded like he would be a considerate conversationalist if you met him at a cafe. You might even hit him up for an extra shot...

The idea for Thirteen Moons came about while Frazier was working on Cold Mountain, which is primarily set in the Civil War years. While doing some research through old North Carolina newspapers circa 190O he came across an article about a white man that had recently died in an insane asylum speaking only Cherokee. Frazier put a bit about it on a notecard but left it aside as he realized it wouldn't have a place in the Cold Mountain story. Sometime later he was thinking on it and came across his notes on the same lone card buried among a number of blank cards.

This man turned out to be a historical figure known to quite a few Carolinians. Frazier adapted much of his life to serve for his main character, Will Cooper - with a dose of other stories, lore and history to alter our hero's path.

In Thirteen Moons, Will, a mere fledgling teen, is sent off (sold into service by his uncle) to run a trading post on the edge of Cherokee hill country. On the way there he finds himself in an all-night card game with drunken half-breeds, hillmen, and Cherokees. Will comes out of it having won the hand of a girl his own age from her father, a renegade Scots-Cherokee Chief. They meet alone for a few brief minutes - before William has to run for his life. What follows next is his gradual immersement in the Cherokee culture.

A page out of the book:

"On dark nights when I lay on my pallet listening to the sounds outside the window, I tried to match the names of creatures Bear had taught me to their various calls and signals. The peeps and creaks of insects and amphibians, a lone night roaming skunk or possum crashing through the bushes as loud as a family of bears or panthers. Night birds in the trees. Martens and minks and other dark-goers stepping crinkly in leaves. One word bothered me especially. 'Yunwi-giski'. Bear said it denoted a cannibal spirit, an eater of men. Bear's people had lived here since some dim elder time and knew this place with an intimacy and depth that could not be improved upon. Why would they bother having such a word if there were no such things as cannibals in the immediate vicinity? Example in point: they had a word for a hog bite. Not two words, one word. Satawa. My opinion was that if hogs are biting you so often that you have to stop and make up a specific word for it, maybe lack of a vocabulary is not your most pressing problem. The other thing that struck me is that this was a language with little interest in abstractions but of great particularity in regard to the things of the physical world. If they had a word like 'Yunwi-giski', how could there not be its physical correspondence out roaming the night woods hunting for the meat of people?"

"But at such times, it always calmed me to remember the girl with the silver bracelets, to think of her scent, the way she stepped inside my big wool coat and shivered against me. Two forlorn children finding comfort with each other. More than once I went and buried my face in the coat's lining, and every time the smell of lavender was fainter than before. As if the girl who had stood within its compass was fading from the world".

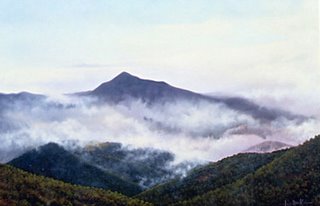

* above; a view towards Cold Mountain today.

No comments:

Post a Comment